Probate is rarely “hard” because any single step is complicated. It’s hard because it is a long chain of steps, many of them dependent on institutions, courts, and waiting periods you can’t control. That combination creates the feeling of spinning your wheels—even when you’re doing everything right.

We’re going to set realistic expectations: what often gets done in weeks, what usually takes months, what causes the worst delays, and what you can do early to shorten the overall timeline.

(This is general information, not legal or tax advice. Probate rules and timelines vary by state and by the complexity of the estate.)

Why probate takes time (even when everyone is motivated)

Probate typically involves some combination of:

- confirming who has legal authority to act (executor/administrator)

- identifying and valuing assets

- notifying creditors and handling valid claims

- paying taxes and expenses

- distributing what remains to beneficiaries

- documenting what happened and closing the estate

Some of those steps are slow because institutions are slow. Others are slow because the law is designed to protect creditors, beneficiaries, and the personal representative from later disputes.

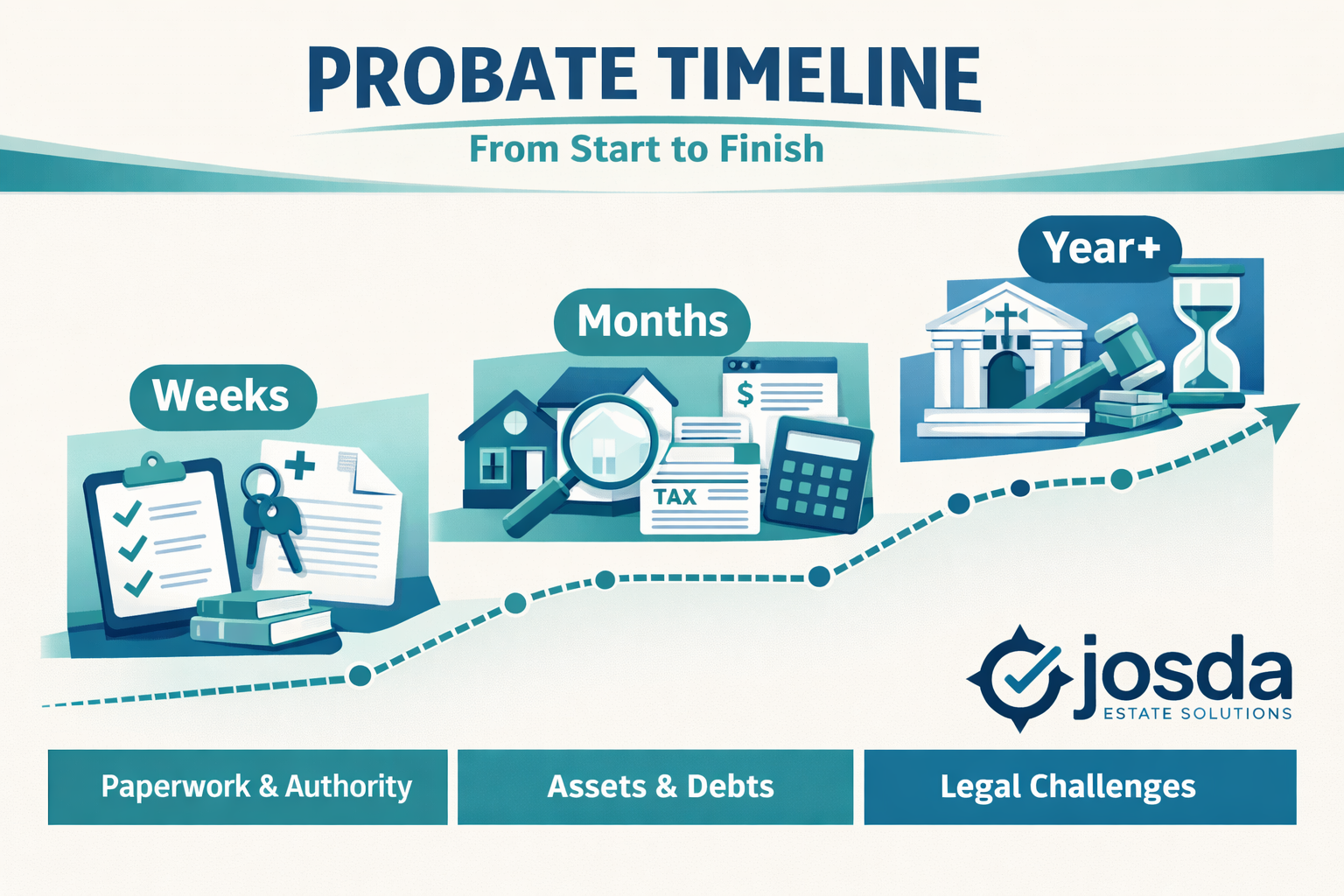

A realistic probate timeline (in plain English)

Weeks: “Open the file” and establish control

In many estates, the first meaningful milestone is simple: getting recognized as the person who is allowed to act.

What usually happens in the first few weeks:

- securing property, keys, and critical documents

- ordering certified death certificates

- locating the will/trust documents (or confirming what exists)

- filing to open probate (if required) and requesting appointment

- receiving court-issued authority (often called “letters” in many states)

- starting an estate activity log and basic inventory

- identifying urgent issues (vacant home insurance, ongoing bills, fraud risk)

Why this phase can stall:

- the will can’t be found (or multiple versions exist)

- family disagreement about who should serve

- court schedules and filing backlogs

- missing death certificates or incorrect personal details that force rework

What to aim for by the end of this phase:

A clear point person, clear authority (or a clear path to it), and a working list of assets, debts, and recurring expenses.

Months: inventory, creditors, taxes, and “real work”

Once authority is established, the estate usually moves into the long middle where most time is spent.

What often takes months (and why):

- Creditor notice and claim windows. Many jurisdictions include formal notice requirements and a period during which claims can be filed and evaluated. Even when everything is straightforward, the process often includes waiting.

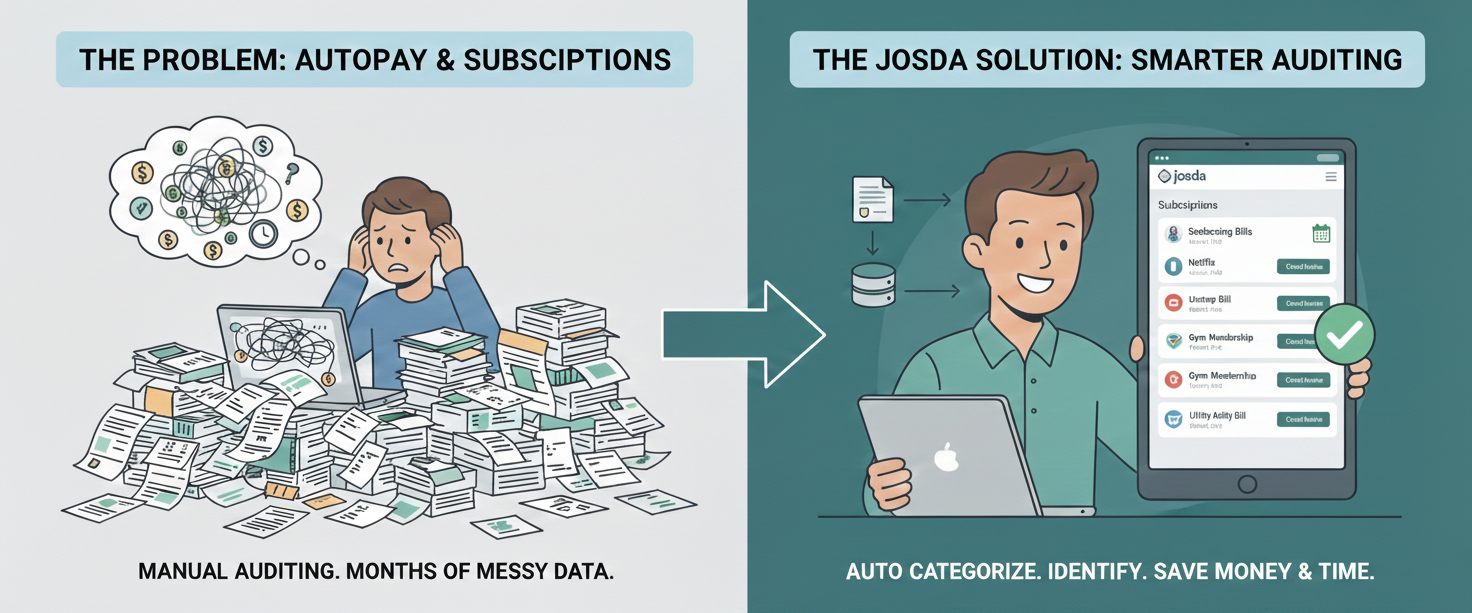

- Asset discovery and consolidation. Finding old accounts, tracking down paperwork, contacting institutions, and gathering statements is slow work—especially if records are incomplete.

- Valuations and appraisals. Real estate, collectibles, business interests, and certain personal property often require appraisals or defensible valuation methods. Scheduling and reports take time.

- Real estate decisions and transactions. Selling a home, cleaning it out, repairing issues, staging, listing, negotiating, and closing can easily push timelines out—especially if court approval is required in your jurisdiction or the market is slow.

- Tax preparation. Final individual tax filings, estate or trust income filings, and related information gathering can take time—particularly if the decedent had a business, multiple income sources, or incomplete records.

- Negotiating and resolving debts. Medical bills, disputed invoices, or unclear debts often require back-and-forth and documentation before anything should be paid.

What to aim for during this phase:

A documented inventory, a documented plan for debts/expenses/taxes, and a clear strategy for any major asset decisions (especially real estate).

The long tail: what pushes probate into a year or more

Most “year-plus” probate timelines are caused by one or more of these issues:

- beneficiary disputes or contested wills

- unclear ownership or title problems (especially real estate)

- multi-state property or multiple jurisdictions

- business interests, partnerships, or complicated investments

- insolvent estates (debts exceed assets) requiring careful prioritization

- missing heirs or unclear beneficiary designations

- litigation or claims that require formal resolution

If any of these conditions exist, the timeline becomes less predictable. The key is not speed; it’s process discipline and documentation.

What you can do to keep probate moving (without creating mistakes)

There are delays you can’t control. But there are also delays families accidentally create. These practices reduce avoidable slowdowns:

- Centralize communication. One point person should speak with banks, creditors, and institutions to avoid contradictory records.

- Maintain an activity log. Track calls, documents requested, expenses paid, and decisions made—this prevents rework and protects you.

- Build a single source of truth. A master inventory of assets, debts, and recurring expenses stops the “we already did that” problem.

- Document before you act. Take statements, photos, and valuations before closing accounts, canceling services, or selling property.

- Avoid commingling funds. Paying estate expenses from personal accounts creates accounting headaches and delays later.

- Treat the house like a high-risk asset. Keep insurance aligned with vacancy rules, prevent damage, and document contents early.

- Set expectations with beneficiaries early. Regular, factual updates prevent pressure-driven decisions and last-minute conflicts.

A simple way to think about “done”

Probate is “done” when:

- valid debts and taxes are handled

- distributions are made according to the plan or court direction

- the estate’s actions are documented (accounting/receipts/releases as required)

- the court (if involved) accepts the closing steps

.svg)