Probate has a reputation for being expensive. Sometimes that reputation is earned. Other times, people hear “probate” and assume it automatically means a giant legal bill—when the reality is more nuanced.

Most probate costs fall into three buckets:

- Court fees (what the government charges to run the process)

- Attorney fees (what you pay for legal guidance, filings, and representation)

- “Everyone else” (the practical costs of managing, valuing, maintaining, and transferring assets)

This post breaks each bucket down so you can build a realistic expectation of what you may spend—and what you can often control.

(This is general information, not legal or tax advice. Probate rules and fees vary by state and county.)

First: what probate costs are (and are not)

Probate costs are typically paid by the estate, not personally by you as executor—meaning they come out of the pool of money and property before beneficiaries receive distributions.

That said, cost surprises still matter because:

- They reduce what heirs ultimately receive.

- They can cause tension (“Why is this taking so much money?”).

- Some expenses require you to front cash temporarily and reimburse yourself later.

Probate costs also don’t always show up as one bill. They often arrive as a long series of smaller expenses spread across months.

Bucket 1: Court fees (the baseline costs)

Court fees are the “admission ticket” to probate. These vary by state and sometimes by county, but they generally include:

Common court-related fees

- Filing fees to open the probate case

- Letters of appointment or “letters testamentary/administration” fees (the documents that prove you have authority)

- Certified copies of court orders (needed for banks, title companies, etc.)

- Publication fees (if your state requires publishing notice to creditors in a newspaper)

- Miscellaneous motion/order fees if you need special approvals (selling real estate, extending deadlines, etc.)

What court fees usually feel like in practice

Court fees are often predictable compared to other costs. They may be a few hundred dollars in some places, and materially more in others—especially where publication or multiple certified copies are involved.

If you want a simple way to think about court fees: they’re usually not the thing that breaks the estate, but they’re always a line item.

Bucket 2: Attorney fees (the cost everyone worries about)

Attorney fees are the most talked-about probate expense because they can range from “reasonable and contained” to “why does this cost more than my car?”

The key is that attorney fees depend less on the word probate and more on:

- how complicated the estate is,

- how organized the executor is,

- and whether anyone is fighting.

Common attorney billing models

Probate attorneys typically charge one of these ways:

- Hourly billing

You pay for time. This is common when complexity is uncertain or disputes are possible. - Flat fee

A set price for a “standard” probate. This is common when the estate is straightforward and uncontested. - Statutory or percentage-based fees (in some states)

Some states allow or prescribe fees based on the value of the estate. This can produce higher fees even when the work is not complicated.

(Even if your attorney quotes a flat fee, ask what’s included and what triggers additional charges.)

What drives attorney fees up

If you want to keep legal spend predictable, watch for these drivers:

- Disputes or high-conflict families

Even mild conflict causes meetings, emails, documentation, and defensive filing. - Missing information

“We don’t know what accounts exist” turns into attorney time spent waiting, re-explaining, and problem-solving. - Unclear ownership or titles

Real estate title issues, unclear beneficiary designations, or joint ownership confusion create extra work. - Insolvent estates (debts exceed assets)

Prioritizing creditors, handling claims properly, and avoiding improper payments can get technical quickly. - Multi-state property

If there’s real estate in multiple states, you may be dealing with additional legal processes.

The honest truth about attorney fees

A probate attorney is usually most cost-effective when:

- you need legal authority quickly,

- legal risk is high,

- or the estate has real complexity.

They are less cost-effective when you’re paying them to be your project manager for dozens of administrative tasks that are not legal in nature.

Bucket 3: “Everyone else” (the costs people forget to budget for)

This is the bucket that surprises most families because it includes the costs of doing the work.

Professional services

- Accountant/CPA fees (final return, estate/trust returns, tax planning)

- Appraisals (real estate, vehicles, jewelry, collectibles, business valuation)

- Financial advisor fees (sometimes involved in liquidating or retitling assets)

- Real estate agent commissions (if a home is sold)

- Property management (if the estate has rentals)

Operations and maintenance

- Utilities on a vacant home

- Insurance (homeowners, vacant property endorsements, auto insurance)

- Repairs and maintenance (winterization, lawn care, cleaning, pest control)

- Storage units (often underestimated)

- Shipping/moving costs (personal property distribution)

- Document costs (death certificates, notary fees, postage)

Payments that feel like “probate costs” but are really liabilities

- Outstanding debts (medical bills, loans, credit cards)

- Taxes owed (income taxes, property taxes, sometimes estate taxes)

- Ongoing subscription charges until accounts are closed

- Refundable deposits you may need to chase down (utilities, rental deposits, etc.)

These aren’t “fees,” but they absolutely change what beneficiaries receive. And they are part of why executors feel like money is leaking out of the estate.

A simple example: why two “similar” probates can cost wildly different amounts

Two estates might both be worth $400,000 on paper.

- Estate A has one home, one bank, cooperative heirs, organized paperwork, and a clear will.

Costs tend to stay predictable. - Estate B has the same value, but the home is in poor shape, one heir is angry, account statements are missing, and there are creditor issues.

The attorney bill rises, the maintenance costs rise, and the timeline gets longer—which creates even more “everyone else” expense.

Same “value.” Totally different cost profile.

What you can often control (and what you usually can’t)

Usually hard to control

- baseline court fees

- required publication rules

- statutory timelines and notice periods

Often controllable

- how organized you are before you start paying professionals

- whether you keep clean records and avoid rework

- whether you prevent property deterioration (vacant home risk is real)

- whether you rush into distributions before debts/taxes are clear

- whether you escalate conflict rather than documenting and de-escalating

A surprising amount of probate cost is friction cost—money spent because information is missing, decisions are rushed, or the process is not being tracked.

Practical ways to reduce probate costs without cutting corners

- Treat this like a project.

Make a task list, track documents, record every call and payment, and keep the estate’s “open loops” visible. - Get death certificates early.

Waiting on certified copies delays everything and can extend how long you pay carrying costs. - Secure and insure property correctly.

Vacant homes and uninsured vehicles create catastrophic downside risk. - Inventory assets and debts early—even if imperfect.

You don’t need perfection to start. You need visibility. - Use professionals for the parts that require professionals.

Pay attorneys for legal work. Pay CPAs for tax strategy. Don’t pay either to hunt for account logins. - Delay distributions until you understand liabilities.

The fastest way to create executor stress is distributing money and then discovering bills and taxes later.

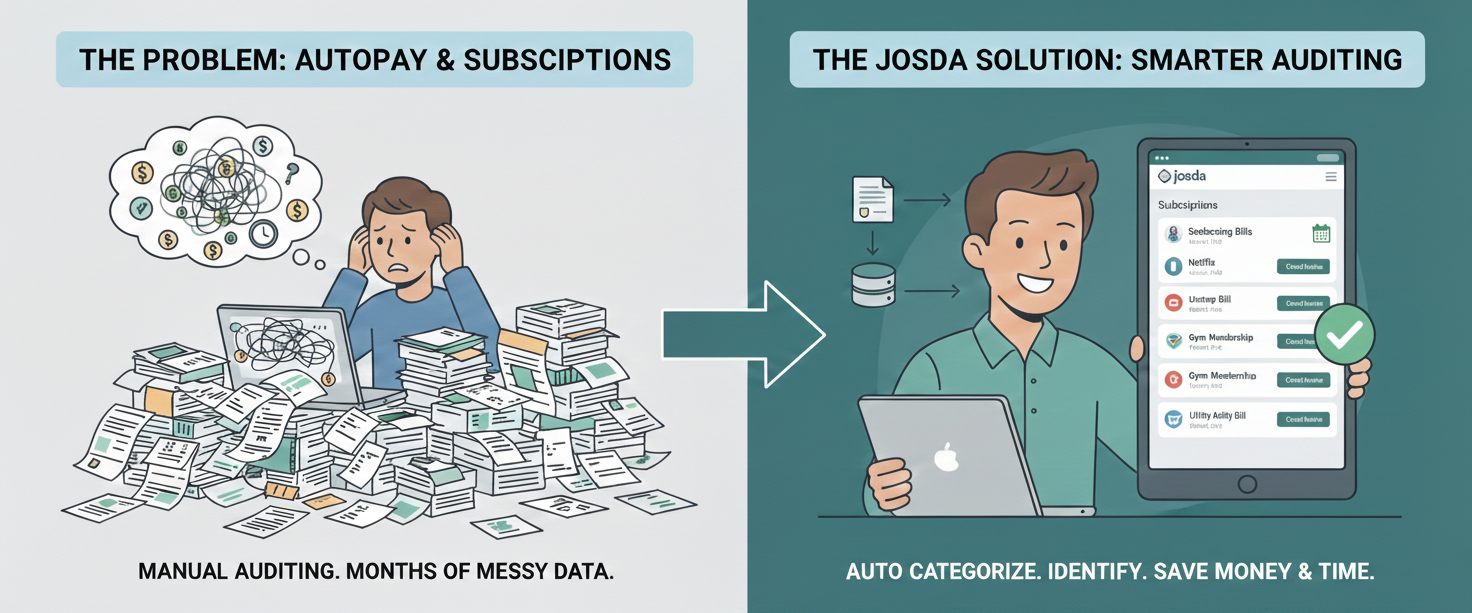

Where Josda fits (briefly)

Most families don’t struggle because a single probate step is “hard.” They struggle because it’s a long chain of steps with paperwork, deadlines, and dozens of small actions that create delays if missed.

Josda is built to help with that “everyone else” bucket—the work that makes probate feel heavy—so legal and tax professionals can be used efficiently, and families can stay organized without living in spreadsheets and email threads.

Bottom line

Probate costs aren’t one thing. They’re a combination of:

- court fees (baseline and mostly predictable),

- attorney fees (driven by complexity and conflict),

- and the operational costs of managing the estate (the silent budget-killer).

If you understand which bucket you’re in, you can set expectations early, reduce surprises, and make smarter decisions about when to hire help.

If you want, share a quick outline of what the estate includes (state, real estate, number of heirs, any conflict, and any major debts). We can help you anticipate which cost bucket is likely to be the biggest and what to do next.

.svg)